As I’ve noted in a few previous posts, the Grimm brothers collected their folk and fairy tales after a traumatic time of national crisis and displacement: the Napoleonic Wars. Thus, even some of their seemingly most cheerful tales reflect fears of displacement and loss. As in “The Town Musicians of Bremen,” on its surface a comedy about four elderly animals who manage to trick a few robbers out of a house—but only on the surface.

The story itself is simple enough. A donkey, realizing that his long term owner is considering putting him down—and presumably either eating him, or feeding him to something else—decides to take off to become a town musician in Bremen. A rather unlikely career choice for a donkey who presumably had never touched an instrument before in his life, and whose bray, by the standards of most people, is rather less musical than, say, pretty much any random instrument played by humans, but the Grimms and their storytellers had presumably seen various traveling animal shows, common before and after the Napoleonic Wars, some of which featured “singing” animals.

We don’t have recordings, but in my imagination, at least, these “singing” animals were fairly similar to the various singing cats now happily meowing away on YouTube. The more things change, the more….you know the quote.

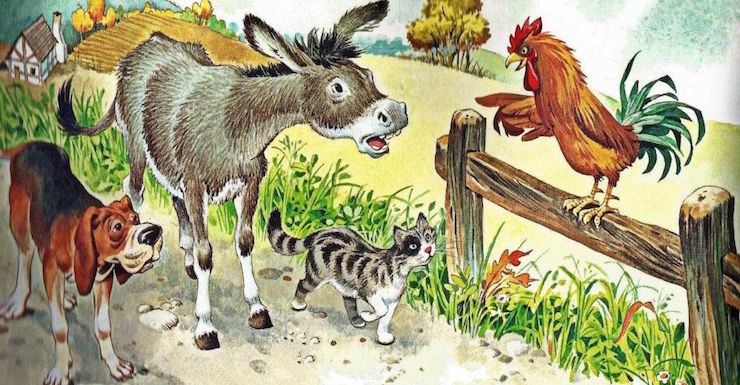

Anyway. The donkey takes off without an issue—presumably, his owner assumed that an elderly donkey was unlikely to run off, so didn’t need to be guarded or tied up, and not worth chasing down once he did run off. The donkey soon encounters a hound, a cat, and a rooster all more or less like him—too old to be useful, terrified of what will be coming up next. In the case of the rooster, the threat is explicit: the rooster is about to be turned into Sunday dinner and some soup. The others just assume that, like the rooster and the donkey, they’re about to be killed, now that they can no longer be useful.

Reading this with a cat flopped over my legs, a cat clearly TOO EXHAUSTED AND OVERWROUGHT to be anywhere else, I find myself wondering exactly how this cat’s human was able to distinguish between “cat preferring to sleep by the fire and spin because he is old” and “cat preferring to sleep by the fire and spin because he’s a cat.” But I digress. This particular cat does admit that he’s not exactly into chasing mice these days, so perhaps his human had a point.

Anyway. Shortly after they meet up and agree to travel together to Bremen to become town musicians, the animals spot a light off in the distance, and head towards it, hoping for food. Instead they find robbers. I need to pause here for another objection: how, exactly, did the animals immediately know that these guys were robbers. It’s entirely possible, animals, that these men were just perfectly honest, hard-working guys who liked to live out in the middle of the woods and accumulate stuff. Unless the house had a sign saying “THIS HOUSE CONTAINS ROBBERS” in which case, I really can’t help but feel that the tale should have mentioned that. Or unless everyone inside just happened to be wearing a pirate costume, which I suppose could happen.

In any case, the animals, sticking with their assumptions, decide that the best way to handle the situation—by which both they and I mean “steal the food from the presumed robbers” — is to scare the robbers off. Which they do by the simple ruse of standing on top of each other and making a huge noise—causing the robbers to mistake the animals for ghosts. The robbers, not exactly the bravest characters to ever appear in a fairy tale, run off. Their captain makes one attempt to return, sending a robber off to investigate—who assures the captain that the house is now filled with a witch (actually the cat), a man with a knife (actually the dog), a black monster (actually the donkey), and a judge (actually the rooster.) This is a bit too much for the robbers, who take off, leaving the house with the animals—who like it so much that they decide to stay there permanently, giving up the idea of becoming town musicians or heading to Bremen.

Left unanswered is what exactly happened with the original owners—unless the original owners were the robbers, in which case, exactly what does that make you, elderly animals? Or just how long the animals could survive on the food left in the house—sure, all of them are old, and the donkey and the rooster can presumably forage for nearby food, but the cat and the hound have already explained that they are well beyond the age where they can reasonably be expected to hunt for their own food.

Granted, with the cat, we are talking about, well, a cat, so it’s entirely possible that the cat is capable of doing quite a bit more than he’s admitting to. This is the same animal who just impersonated a witch, after all.

But unanswered questions or not, they have a home, however, shall we say, questionably obtained.

For all of its implausible elements, “The Town Musicians of Bremen” represents the unfortunate reality facing Germany during and immediately after the Napoleonic Wars. On a purely immediate financial level, the wars left Germany impoverished, with lower and middle class families suffering severe deprivations and often starvation. Several Germans, fighting either for various Germany armies or forcibly conscripted into Napoleon’s Grand Army, were permanently disabled by various war wounds and/or diseases caught while on the march. Often unable to work, several Germans faced homelessness and potential death—just like the animals of the tale. In some cases, they headed to cities hoping to find work or charity—again, much like the animals of the tale. In at least a few cases, soldiers—French, German and Russian—sent residents fleeing from their homes in fear.

All of this is reflected in the tale. But for all of its acknowledgement of disability, aging, and homelessness, “The Town Musicians of Bremen” presents a hopeful picture: that of characters perceived as useless who, when it comes right down to it, are not just able to take long trips and try out new careers, but able to drive out armed robbers from a house. It also offers the assurances that those no longer able to fight (or, in the case of the cat, claiming to be unable to fight) can still defend themselves in other ways—through trickery and intelligence. Getting turned out of a home isn’t the end, the tale suggests. If you are willing to try something new.

When read out loud by the proper sort of parent or reader—that is, the sort who can make funny rooster sounds—”The Town Musicians of Bremen” can be very funny, which presumably helps to account for its popularity. It helps, too, I think, that the story can be and has been so easily adapted to other formats. Several musicals, animated films, and at least one Muppet version exist, as well as several outstanding picture books, and various statues of the four animals standing one on top of another in various places throughout Europe, spreading knowledge of the tale.

But I think that “The Town Musicians of Bremen” has survived largely because it is such a comforting story: a tale where dangerous robbers can be chased off by elderly animals, a story that assures us that what looks like a dangerous witch is nothing more than a lazy, elderly cat, and above all, a tale that promises us that yes, even those turned out from their homes for infirmity or other reason can still fight, and can still find a home. It was a message badly needed in the post-Napoleonic period, and a message that still resonates today.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.